Being an autistic person of colour

I was diagnosed as autistic one year ago, at the age of 18. Growing up, seeing everyone around me get on fine made me feel alien. Social interaction was a foreign concept to me: something I had to study like a specimen under a microscope. Even after years of practice, every conversation I had felt unnatural and rehearsed. Speaking verbally was never my strong suit, so even if I had the courage to speak, I could never articulate my feelings in the way I wanted to. Writing, an interest of mine from a young age, could have helped me communicate, but I feared judgement from others.

Another issue I faced was not being understood. I grew up in a Ghanaian household where any non-visible conditions such as being neurodivergent or mental illness were a taboo. As a result, my meltdowns and social communication issues weren’t understood. It didn’t help that I had well-behaved, smart, ‘normal’ older siblings. My eldest sister suggested I was merely shy, like her, but I knew there was more to it. However, I simply concluded that I was the problem.

These experiences caused a dip in my self-confidence. This followed me in my school life; I seldom spoke except in a small, shaky whisper, bowed my head and never contributed in class. I didn’t have any friends until around Year 13, and even then, I observed and listened more than I spoke. If not ignored, fellow students would ask me why I was so quiet, and teachers would pick on me for my inaudible voice and tendency to shudder. Being singled out so often reinforced my belief that the problem was me.

Seeking an autism diagnosis

Around the age of 12, I saw a therapist for the first time. Desperate for some kind of explanation, I looked forward to it. However, because I struggled to speak, my sessions were mostly long silences. I would have preferred being asked questions or writing answers down, but I was denied any alternative. The therapist told my parents that she didn’t know what to do with me, which hurt. My next therapist struggled to connect with me in a similar way but was a little more helpful, later being the one to refer me to an autism specialist.

Autism wasn’t new to me, but I never related to it. In media, autism was presented as a condition only affecting children – the most common stereotype being young white boys. When my eldest sister told me she thought I might be autistic, I nodded but dismissed it. In my head, I didn’t look the part. The poor representation also made me think autism diagnosis was some kind of checklist. Special interests? Check. Inability to tell apart expressions…I didn’t fit that; I must not be autistic. Even when I was referred, evaluated and awaited the results, I still doubted the possibility despite glaring signs.

In fact, I didn’t fully accept myself until I sought out autistic communities through forums and online networks after my diagnosis. People, of all races, ages and genders shared their special interests, what overstimulated them and how they regulate themselves. I especially liked female specific forums (though discussions between autistic people of colour are less common in my experience). It was like unlocking a new world; in a short time, I went from feeling isolated to understanding myself a lot more. My brain works a little bit differently from other people and most importantly, there are many people like me.

Diversifying the view of autism

Whenever I remember my diagnosis day, I feel a mix of emotions: relief that I found an answer and a combination of sadness and anger at everything I had to endure. In hindsight, it was all so clear that I struggled, and I could have been diagnosed much earlier. Looking back, I can conclude that I would have had an easier time if there was more welcoming of difference as well as understanding that autism is not a monolith. Women, adults and ethnic minorities can be autistic too. I hope my story can help diversify the view of autism. People like me should not have to struggle for as long as I did without the necessary support.

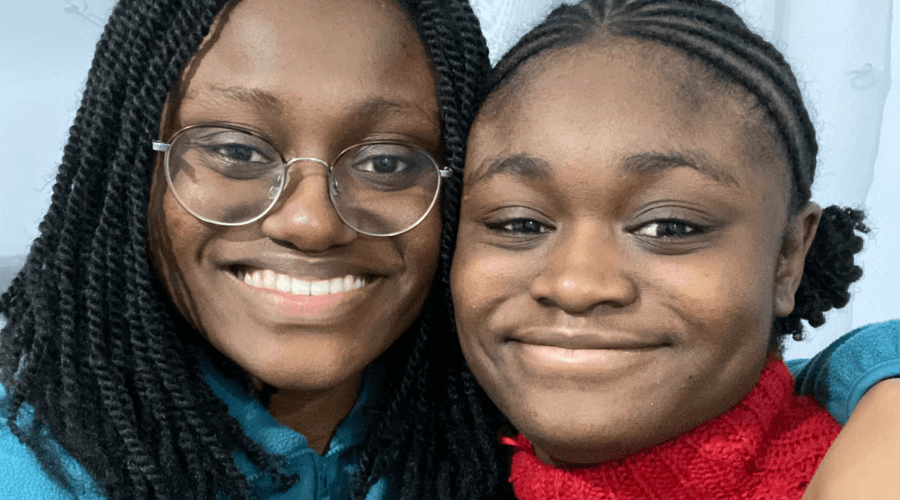

About the author

Nana-Yaa Bediako is an autistic 19-year-old from North London. They are currently on a gap year, after finishing their A-Levels, to work on a portfolio for a graphic design degree. Their hobbies and interests include reading, writing, graphic design and listening to music.

Vanish are donating 25p from every pack of Vanish Gold Range sold in UK Asda stores between 29th March and 18th April to Ambitious about Autism, to help create a world where autistic girls and young people are heard, included and supported.

Vanish have provided neurodiversity training to their employees and talent and acquisition teams to establish more inclusive hiring policies. Alongside the creation of an internal neurodiversity handbook. They will also offer employee volunteer days with Ambitious about Autism to continue to build an ongoing relationship, having committed to 3 years of activity for World Autism Acceptance Week.

Vanish is committed to helping clothes live longer and believe that every garment you own should bring you comfort again and again. Find out more about our #Rewear fight here.